Confirmation Methods for Central Venous Catheterization

The spread of ultrasound devices has reduced the frequency of mechanical complications. However, critical situations can arise when mechanical complications occur. In a 2004 report, the central venous catheter-related mechanical complications with the highest mortality rates were pulmonary artery damage, hemothorax, cardiac tamponade, and air embolism, in that order.

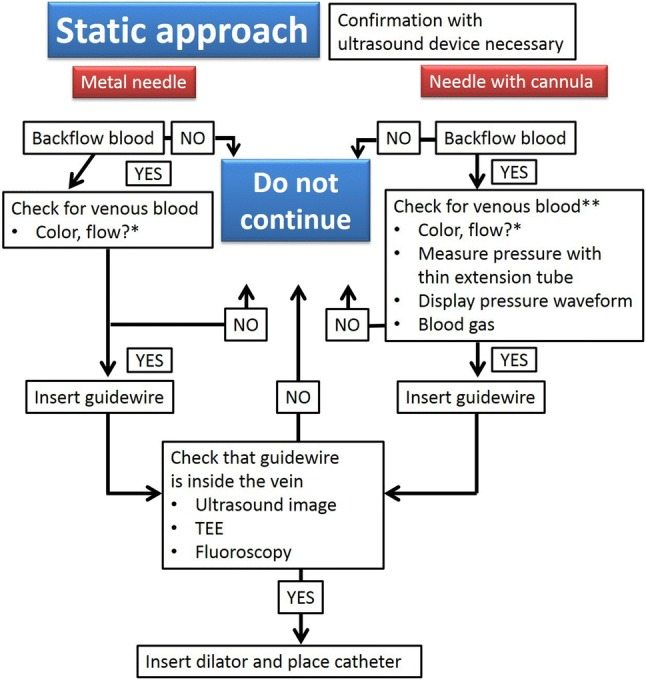

Any of these complications could lead to death or a critical situation. Great care should thus be taken to ensure these complications in particular do not occur. To achieve this, place the catheters in the appropriate location and ensure that a dilator or catheter is not mistakenly inserted into an artery. Ultrasound-guided central venous catheterization has been reported to reduce the frequency of mistaken arterial puncture.The preferred confirmation methods for ultrasound-guided central venous catheterization are shown in the following figures. Figure 1 addresses the static approach. Basically, ultrasound images are not used during puncture in the static approach; thus, it is important to check that the puncture needle is definitely in the vein. Inserting a cannula into the vessel allows manipulations to be performed stably. It is possible to mistake arteries for veins with signs such as the color and force of backflow blood with hypoxemia, extremely high oxygen partial pressure, or hypotension, such as in states of shock. It is easy to measure pressure by attaching a small extension tube, by displaying the pressure waveform to confirm the presence of a venous pressure waveform, or by taking a blood sample for blood gas analysis to confirm venous blood. One of these methods is necessary to confirm that the needle is inside a vein. As described in the section on puncture techniques, as it can be difficult to confirm that the punctured vessel is a vein with the metal needles that are used in the static approach, the use of a cannula needle is recommended. Therefore, if a metal needle is selected with the static approach, ultrasound images or other examinations should be used to confirm that the inserted guidewire does not penetrate the posterior wall and is traveling inside the vein. Even if a cannula needle is used, it is preferable to confirm through ultrasound images or other examinations that the inserted guidewire does not penetrate the posterior wall and is traveling inside the vein.

Central venous catheterization methods with a static approach. *Venous blood cannot be confirmed using only the color or flow of backflow blood. **Insert the guidewire about 10 cm and insert the cannula up to its base, then confirm by attaching an extension tube to measure pressure, display a pressure waveform, or perform blood gas analysis. TEE, transesophageal echocardiography

Figure 2 addresses the real-time approach. With this approach, ultrasound is used to confirm that the needle is inside the vein, regardless of whether a metal or cannula needle is used. With a metal needle, once the color or force of the backflow blood indicates the presence of venous blood, the guidewire can be inserted. After confirming in the ultrasound images that the guidewire did not penetrate both the anterior and posterior walls of the vein and is traveling inside the vein, the dilator can be inserted. If a cannula needle is used, once the color and force of the backflow blood indicate it is venous blood, the guidewire can be inserted. Then, similar with a metal needle, after confirming in ultrasound images that the guidewire did not penetrate both the anterior and posterior walls of the vein and is traveling inside the vein, the dilator can be inserted. If it is difficult to make a decision based on the backflow blood, insert the guidewire about 10 cm and insert the cannula up to its base, then, as in the static approach, confirm the presence of venous blood by attaching an extension tube to display a pressure waveform or for blood gas analysis.

Then, insert the guidewire. After this, confirm in the ultrasound images that the guidewire does not penetrate both the anterior and posterior walls of the vein and is traveling inside the vein, then insert the dilator. Figures 1 and and142 show ultimately only safety examples; thus, each institution should reference these to establish methods for confirming that a dilator has not been mistakenly inserted into an artery.

Confirmation of central venous catheterization with real-time approach. **Insert the guidewire about 10 cm and insert the cannula up to its base, then confirm by attaching an extension tube to measure pressure, display a pressure waveform, or perform blood gas analysis. TEE, transesophageal echocardiography

Figure 3 shows the extreme importance of confirming in ultrasound images or other methods that the guidewire does not penetrate both the anterior and posterior walls of the vein and is traveling inside the vein. The following describes the methods for confirming in ultrasound images that the guidewire is traveling inside the vein. After inserting the guidewire, the short axis will look like the image in Fig. 3a. However, it cannot be declared that the guidewire is traveling inside the vein from this alone. This is because the possibility that the guidewire has penetrated the vein cannot be ruled out. Thus, short-axis images must be observed by moving the ultrasound probe slowly from the guidewire puncture site toward the heart to around the clavicle. This will show that, in most cases, if the guidewire penetrates the skin and enters the vein, it proceeds almost as if it is in contact with the vessel wall. Next, if possible, the tip of the guidewire should be depicted in a long-axis image. As shown in Fig. 3b, if it can be confirmed that the guidewire tip is traveling along the vein parallel to it and without any changes in angle, it is acceptable to believe that it has not penetrated the vein. This confirmation procedure is extremely important for preventing mechanical complications.

Confirmation of guidewire location using ultrasound images. The patient was a 6-month-old infant. The guidewire can be seen inside the internal jugular vein in the short-axis image (a). However, this alone cannot determine if the guidewire tip is inside the vein. The long-axis image shows that the guidewire path gradually becomes parallel to the vessel wall (b)

Source: Safety Committee of Japanese Society of Anesthesiologists