Continuous Normokalemic Coronary Perfusion:

Empty Beating Heart

Early intracardiac procedures were performed on normothermic, perfused, empty beating hearts. Experimental studies initially suggested that this method maintained "normal left ventricular function" for up to 3 hours of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) with the heart empty and

beating.

However, current evidence shows this approach has limitations. Water accumulates in the myocardium during CPB, reducing ventricular distensibility by about 50% after 3 hours and leading to abnormal coronary blood distribution. Changes in myocardial compressive forces and left ventricular geometry can hinder intracoronary collateral flow to potentially ischemic areas. Reports indicate a 15% incidence of transmural myocardial infarction with individual coronary artery perfusion during aortic valve replacement, with 70% of patients showing signs of myocardial necrosis—comparable to those undergoing cold ischemic arrest.

Despite these issues, this method can be effective for various procedures and may be combined with other myocardial management techniques. For instance, in elderly patients or those with significant aortic arteriosclerosis, CABG using both internal thoracic arteries can be performed with stabilizers and peripheral cannulation without aortic clamping. This "no-touch" technique has been shown to reduce intraoperative and postoperative strokes.

Mild or moderate hypothermia is often used with this method. McGoon and colleagues reported successful outcomes in 100 consecutive isolated aortic valve replacements using this approach, with no hospital deaths, demonstrating its potential for good results when properly applied.

Perfusion of Individual Coronary Arteries

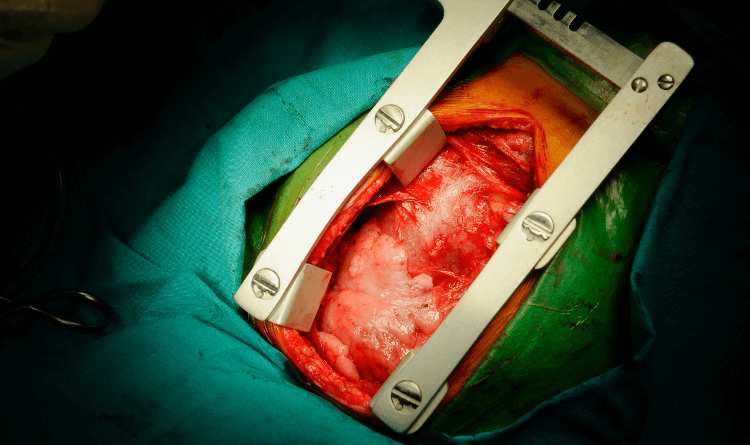

For aortic valve surgery, individual coronary artery cannulation is essential to perfuse a beating heart. After establishing cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and clamping the aorta, small cannulae are inserted into the right and left coronary ostia to deliver blood through separate pumps. The tips of these cannulae are 3 to 4 mm long.

While this method is effective for most patients, it has limitations. The cannula may extend past the bifurcation of the left main coronary artery, leading to perfusion of only the left anterior descending or circumflex artery. In about 1% of cases, these arteries arise separately from the aortic sinus, complicating cannulation. Patients with left dominant coronary systems, often seen in those with congenital bicuspid valves, have shorter left main coronary arteries, which further complicates perfusion. Additionally, in around 50% of patients, the conus artery supplying the right ventricle is not perfused by the right coronary cannula. Mechanical damage to the coronary ostia during cannulation can also cause myocardial infarction and late coronary stenosis.

The procedure can lead to periods of global myocardial ischemia between aortic clamping and the start of coronary perfusion, typically lasting 2 to 3 minutes. Blood leakage around the cannulae might require brief pauses in perfusion.

Maintaining a flow rate of 200-250 mL/min is crucial. This flow rate, lower than 300 mL/min, prevents myocardial damage while avoiding vasoconstriction and underperfusion. The perfusate should be warmer than 30°C to keep the heart beating, as persistent ventricular fibrillation increases the risk of perioperative infarction and death.

Hypothermic Fibrillating Heart

In continuous coronary perfusion with ventricular fibrillation, the fibrillation can be sustained by an electrical current if perfusion is at 37°C. Alternatively, it may be induced and maintained spontaneously or electrically with moderately hypothermic perfusion (25°C-30°C), which is preferable. Perfusion can occur via the intact aortic root, as in CABG, or through individual coronary cannulae during aortic valve replacement.

There are theoretical concerns with this method. For instance, subendocardial perfusion may be compromised during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and ventricular fibrillation, especially in hearts with ventricular hypertrophy. Nonetheless, good clinical outcomes have been achieved using either normothermic CPB with electrically maintained fibrillation, moderate hypothermia with fibrillation sustained by hypothermia alone, or profound hypothermia with fibrillation. Akins has reported excellent results with CABG using profound hypothermia and fibrillation. Although time limits are a factor, not well-defined, this method generally offers better surgical conditions than a beating heart but is often considered less ideal than a cardioplegic technique.