Mechanical Complications of Venous Catheterization and their Countermeasures

Arterial puncture and hematoma

Central venous catheterization rarely accompanies the formation of hematoma. However, with the jugular vein, and particularly when the carotid artery is mistakenly punctured, the formation of a hematoma may block the upper airway. If an artery is mistakenly punctured during SV puncture, external compression to stop the bleeding can be difficult to apply. If a catheter of 7 Fr (equivalent to a diameter of 2.3 mm) or less is inserted into an area, where compression is possible and the catheter can be withdrawn and external compression applied for 10 min, then it can be withdrawn with no problem. In other words, if an artery is mistakenly punctured by a needle thinner than 14 G (equivalent to a diameter of 2.1 mm), hemostasis may be possible via compression. However, if a catheter or dilator larger than 7 Fr is inserted into an artery or a vessel for which compression is not possible, a cardiovascular surgeon should be brought into withdraw the catheter safely; otherwise, cerebral infarction, arteriovenous fistula, or hemothorax might result.

Pneumothorax

Understand the local anatomy and do not insert puncture needles into risky areas. When performing catheterization, diagnose any cough, chest pain, or respiratory difficulty from auscultatory findings and chest radiographs. Immediately after catheterization, a normal chest radiograph will not rule out pneumothorax. Delayed pneumothorax sometimes occurs. In most cases, pneumothorax that fills about 30% or less of the chest cavity does not present with clinical symptoms and does not normally require drainage. Recent findings have indicated that ultrasound devices can be useful in diagnosing pneumothorax.

Hemothorax, mediastinal hematoma, pleural effusion, and cardiac tamponade

Particular caution is warranted in patients who require multiple punctures. Subcutaneous diffusion of transfusion fluid can result from catheters during insertion or clinical use or from damaged blood vessels, which can create local tissue edema. Extravasation of fluid that has been injected into a vein may cause pleural effusion. Moreover, punctures in the pericardium can cause cardiac tamponade, which has a high mortality rate. These require drainage of the chest cavity, mediastinum, or pericardium.

Air embolism

This is caused when air mistakenly enters the vessel through a puncture needle or open catheter end exposed to the open air. Puncturing should be performed in a head-down tilt or the Valsalva maneuver should be added, if necessary, in horizontal supine position. After a catheter is removed, air can be drawn into the puncture hole to cause an air embolism. Therefore, after removing the catheter, cover the puncture site with a transparent dressing or other covering.

Arrhythmia

Mechanical stimulation from a guidewire or catheter can cause arrhythmia, including supraventricular arrhythmia and ventricular fibrillation. Rarely, a patient can transition to continuous ventricular fibrillation when a catheter is removed. In such an event, immediate defibrillation should be performed.

Local nerve damage

Local nerve damage related to catheterization can present as mechanical injury, nerve compression from a hematoma, or neurotoxicity from medical fluids leaking outside a vessel.

Rare complications

Rare complications include brachial plexus injury, thoracic duct damage, or chylothorax from left IJV or left SV puncture. Knotting of the catheter, a guidewire being left behind, accidental removal, femoral nerve damage from FV puncture, abdominal cavity puncture, and retroperitoneal hematoma may also occur.

Frequency of complications

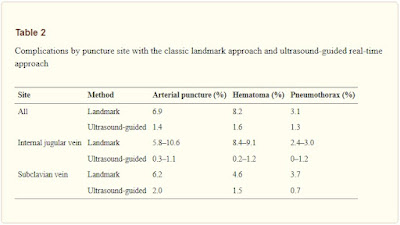

Table shows the frequencies of complications by puncture site with the classic landmark approach without using ultrasound images and with the ultrasound-guided real-time approach

The results of a meta-analysis showed that catheterization failures were significantly less frequent for the IVJ and SV with the ultrasound-guided approach than with the landmark approach, but the difference for the FV was not significant. PICC can also be useful in patients such as those with the risk factors discussed below.

Catheter insertions and removals should be recorded on the hospital’s designated forms and surveys should be performed to ensure that central venous catheterization is monitored for safety.

Risk factors

Patient risk factors for mechanical complications include underlying disease, comorbidities, tendency to bleed due to regular medication or other factors, high risk for thromboembolism due to arteriosclerosis, and changes to the anatomical pathways of vessels due to surgery or bone fracture.

Factors that can increase moderate levels of risk include (1) puncturing the site of a previous central venous catheterization, (2) history of local radiation therapy, (3) history of median sternotomy, (4) recent myocardial infarction, (5) thrombocytopenia, (6) venous thrombosis at the puncture site, (7) fibrinolytic therapy, and (8) an anxious patient. Factors that can increase mild levels of risk include (1) abnormal weight/height ratio, (2) severe obesity, (3) prolonged coagulation time, (4) artificial respiration with high airway pressure, (5) moderate to severe arteriosclerosis, (6) sepsis, (7) ventricular arrhythmia, (8) pulmonary emphysema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and (9) hypovolemia.

Source: Safety Committee of Japanese Society of Anesthesiologists